“American Psycho:” Misunderstood Masterpiece

Last summer, I had the absolute treat of seeing Mary Harron’s “American Psycho” in theatres for a special screening. I was in the indie theatre I frequent, and the room the theatre reserves for special screenings is especially tiny — there were only about 40 or so seats in the entire theatre. The screening was full, though, for a movie that came out 23 years ago. The audience seemed to be split between people who had been wanting to see the film for a long time and diehard fans. Regardless of if they had seen it or not, the excitement in the room was palpable. Everyone knew what they were in for, and after witnessing how successfully this film landed, I’m even firmer in my belief that “American Psycho” only gets finer with age.

Written by Brett Easton Ellis, “American Psycho” was initially deemed unfilmable due to its severe violence and graphic sex. The novel had been controversial since its release in 1991, but producer Edward R. Pressman bought the film rights a year later and was determined to have it adapted.

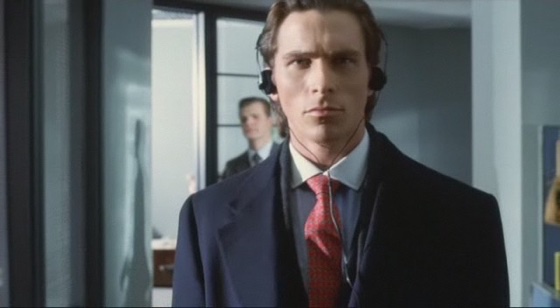

Development was shaky. Once Harron was attached to the project, she cast Christian Bale as her nightmare protagonist we all know and love, but the film’s distributor had wanted Leonardo DiCaprio in the role and chose instead to just fire Harron from her own script. Funnily enough, DiCaprio backed out of the film because of how controversial the novel was, and Harron was rehired on the condition she could guarantee Bale in the part instead. This decision makes this film. Any actor other than Bale would not have been able to nail the believable hotness and obvious clownishness of protagonist Patrick Bateman.

Bateman, is a New York City investment banker at the peak of his life and career in the 1980s. His primary interests are murders and executions. The film is a few weeks in his life, punctuated by about what you would expect — cocaine, fancy dinners, affairs, and murdering people he deems inferior. The entire film is a condemnation of this type of man — nearly every single one of Bateman’s colleagues finds him pathetic and insufferable and tells him this to his face. Despite how heavy-handed the portrayal of toxic masculinity is through Bateman, people somehow still miss it (note the influx of Patrick Bateman Chad memes, which are funny ironically, but just like with the film they’re based on, people completely miss the irony). There’s an ongoing debate about depiction equaling endorsement or fetishization in film, a debate that’s been going on for a century and won’t end anytime soon. “American Psycho” is a prime example of this debate, in my opinion — the actual film itself is not too graphic with the exception of a few scenes, but even then, those scenes are not more gory than the violence in any Scorsese movie, although they are definitely more viscerally disturbing (which is why people see it as more controversial than other films, despite much of the violence being entirely offscreen).

The novel and the film adaptation are quite different, tonally. The book is played much more straight, with less (intentional) humor and significantly more graphic scenes. I know a few people who love the film and are eager to read the novel, which they should, but it is a BIG mistake to think you’re in for something as enjoyable and fun as Harron’s film. It is still worth your time though — in talking about the novel and film’s reputation and controversy surrounding its treatment of female characters, sexuality, queer characters and EVERYTHING else (this movie has a lot going on) a lot of the focus tends to be placed on Harron and Turner’s writing presence as women (which it should be, their script is, in my opinion, an absolute improvement over the original novel), with a lot of the controversy falling on Ellis’ novel. I personally think writing off the novel as graphic garbage is unfair. Ellis is a gay man, and there’s something more there than just the shock factor. The satire is just handled differently (and, in my opinion, better) by Harron and Turner.

Harron’s directorial debut covered the partially untrue narrative of Valerie Solanas’ failed assassination of Andy Warhol, and her work prior to and following “American Psycho” frequently focuses on themes of feminism, sexual empowerment, and complicated female characters whose stories are often told with a good deal of compassion. Turner, her frequent collaborator, is a lesbian writer and actress and icon of independent queer 90s cinema (she also acts in addition to co-writing “American Psycho” and has a really funny in-joke where her character denies being a lesbian despite her going to Sarah Lawrence, which is also Tuner’s alma mater). Both of their experiences and politics add a lot to “American Psycho,” and their contributions make a film that many write off as gory, problematic, and vulgar, something much more special than even Ellis’ novel.