St. Lawrence University is My Home… Where Are My Family Pictures?

All photos courtesy of Ndirangu Warugongo ’18

The premise of this piece was initially meant to focus on the lack of iconographic representations in our SLU community. The concern came to my attention as I began to consciously walk around our campus in an attempt to create closure and reflect on my four years on this campus.

I have been part of the SLU community (in the form of the Kenya Semester program) since I was four years old; needless to say, in many ways, SLU is my home. So, you can imagine the shock and awe I felt when I arrived on campus to discover that the alien status marked on my visa would characterize my experience.

Six months after I was born, the world welcomed another young black baby: Michael Brown. My dearly departed brother and I grew up worlds apart, a distance dwarfed by the feeling of fraternity I hold, which was most emblematically articulated by the shared affection Chinua Achebe expressed upon meeting James Baldwin, who referred to Achebe as “a brother he had not seen in four hundred years.”

August 9, 2014 marks the day I arrived in this country in pursuit of my “American dream.”

But this day also marks the end of Michael’s. On this day, he was gunned down by those who had vowed to serve and protect him but instead functioned as judge, jury, and executioner. It would be disingenuous of me to say that I can relate to the pain and heartbreak that his family and friends endured. However, after this day, I too was drawn to the national, if not global, call for the dignity and value of the brother I never met and the countless others whose lives do not matter.

“Black lives matter” became the call of our generation, an expansive modern-day articulation of the sense of alienation that greeted me as I was “randomly” selected for screening in Nairobi, London, and Chicago. A cry of pain for the loss of those whose original sin was the color of their skin and a demand for the freedom of self-actualization, void of the parameters of class, race, gender, sexual-orientation, ability, and place of origin.

Orientation Week encompassed a lot of games, and while I was perturbed by the amount of playing that jet-lagged and nervous adults were expected to participate in, I understood their purpose of getting to know one another and building a sense of shared community and identity.

So, we jumped and hopped and said each other’s names, with the hope that friendships would be created and community would be fostered. But when the ceremonies and festivities ended, and the mandatory interactions elapsed, I became acutely aware of the awkward smiles and genteel nods coupled with the deliberate aversion of eye contact from some of the people with whom I had been holding hands and singing with only days earlier.

I became aware of the events I was welcomed to, the classes where I could openly share my positions, and the areas in Dana where I was greeted with smiles rather than nervous glances. In short, I became aware of my own presence and the weight that it carried to alter the mood of a space.

Nevertheless, I ventured to Java, Fall Fest, Spring Fest, and the townhouses. I took theater classes, showed up to awkward club meetings, I played on the rugby team, and even tried my hand at football. But despite this, I can safely say that it became apparent to me that SLU was not designed for me or at least not for someone who looks like me.

With that said, it comes as little surprise that organizations that I happily paid for to tailor my SLU experience have taken little to no regard for who or what might best represent my – or rather our (non-white students’) – interests on campus. It comes as no surprise that students of color are expected to carry around receipts of racial discrimination and create public spectacles for their concerns to be considered legitimate.

Lastly, it comes as no surprise that while Thelmo voted to open up an investigation for racial discrimination to be looked into, it will be carried out under the premise of racism existing void of racists. It is at this point that I am obliged to clarify that I do not hate anyone or think of them as vile, disgusting people who have a sinister hatred for people of color.

But without appropriately identifying the actions of individuals and the underlying ideologies that informed them, we lose sight of the expanse of this issue and fall back on the comfortable and woefully ineffective expressions that have come to embody our deliberation over this topic.

We use phrases like “white privilege,” “inclusion,” “diversity,” and “intersectionality” as buzzwords that assuage the violence of racial acts while giving white and non-white students alike little “woke passes,” which we can whip out at the slightest challenge of unfair or unjust treatment. We can prescribe these words to people who might feel sick under the weight of alienation and tokenism, without challenging the individuals who create, maintain, and exacerbate these feelings to begin with.

We can discuss “privilege” as an inherent and unfortunate reality rather than asking which undeserved opportunities people received because of it, and we can tackle “inclusion” without asking who owns and tailors the spaces we are discussing. We can hide behind satire and free speech as we mock the frightening, humiliating, and life-threatening experiences people face each day without talking to them.

We can travel to “Africa” and take pictures with children that “change our life,” without ever stepping foot into an African Students Union meeting. And if this fails, we can apply them to everyone to mitigate the varied and intense nature of these experiences, because at the end of the day, aren’t we all diverse? Don’t we all have privilege? Isn’t each one of us qualified to join the “Oppression Olympics,” as Mr. Banta calls it?

St. Lawrence was established in 1856, fourteen years before the Fifteenth Amendment recognized me as a human being and over 100 years before the Civil Rights Act and the independence of my nation from barbaric racialized British imperialism.

It also sits, as the Native Americans whose reservation I had the privilege of visiting recently reminded me, on colonized land. It should therefore not be shocking that this school was not created for non-white students. But St. Lawrence is my home, and a place I dearly care about.

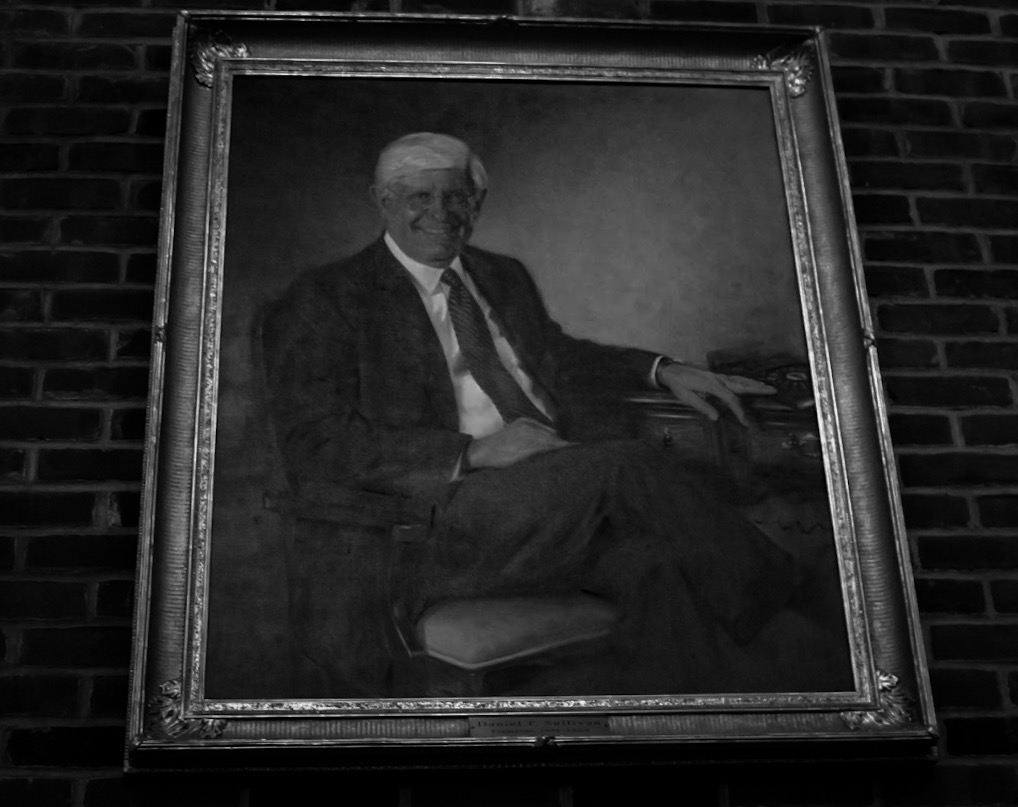

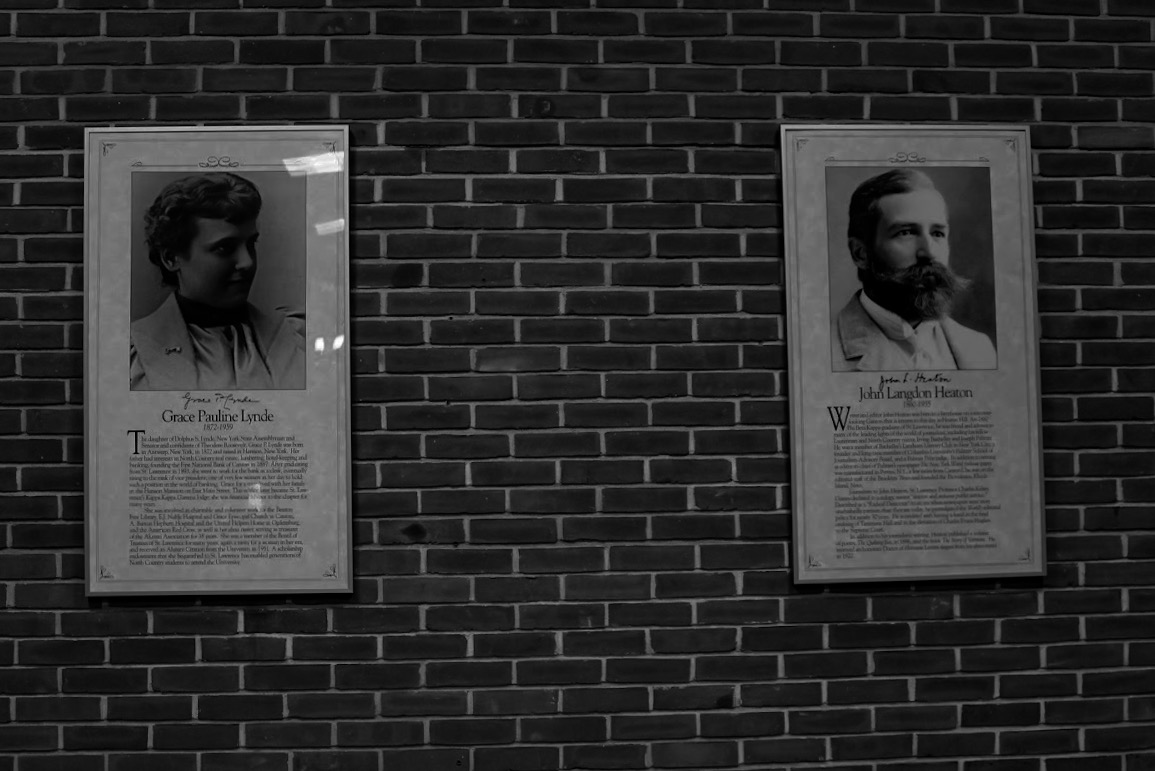

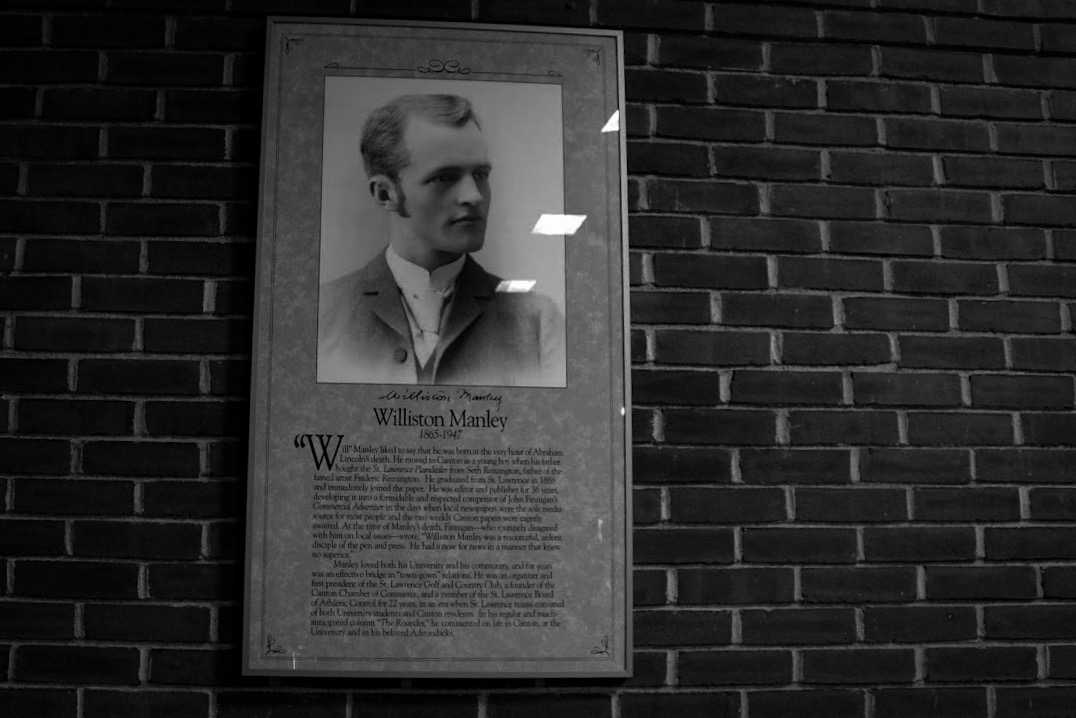

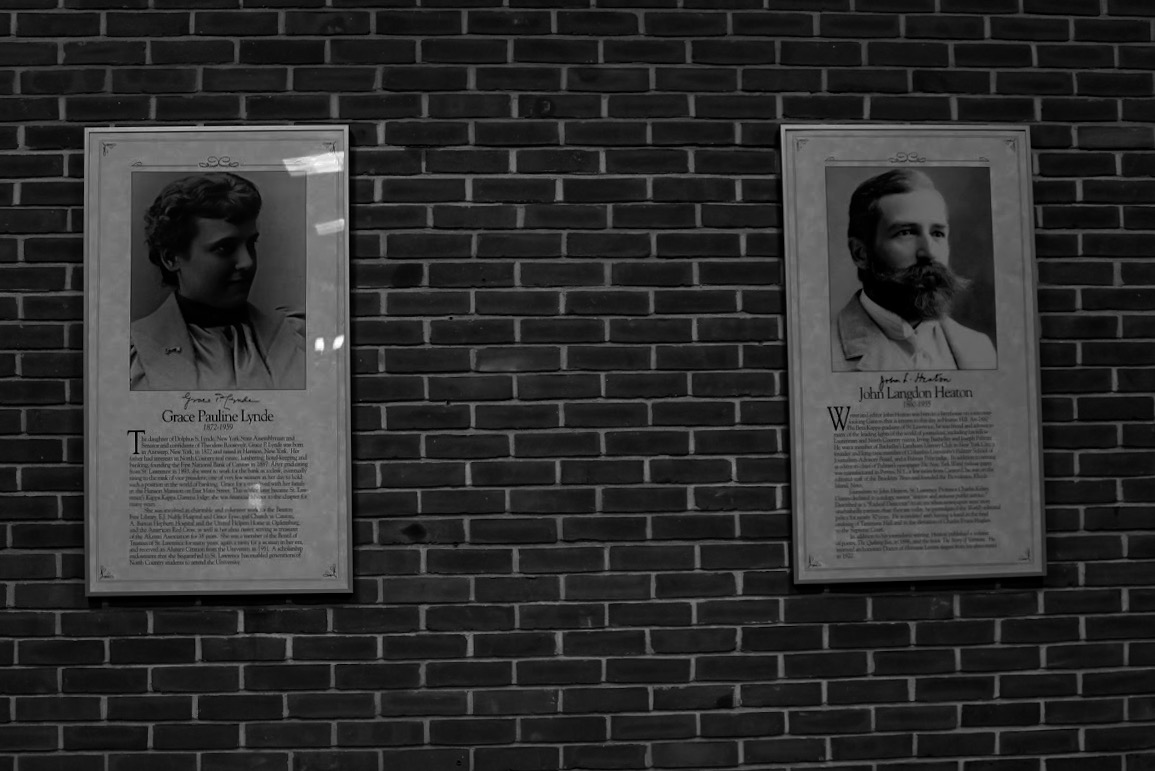

Yet as we look across campus and celebrate those who have contributed to the fabric of our community, one that I have come to love and continue to call my home despite the numerous flaws, I am overwhelmed by the racial homogeneity of the pictures around campus. I simply wish that there were more pictures of the numerous people from around the world, that have made this campus and my experience truly memorable.

While I understand the power of diverse iconographic representation, made evident by the financial success of Marvel’s Black Panther

, it seems unfortunately fitting that the current homogeneity stands as a reminder of how much honest introspection our community needs to do before we can begin answering the difficult questions before us. As for now, I will continue to walk around the place I have come to call my home, silently thinking: where are my family pictures?