We Need You Listen: International BIPOC Experience

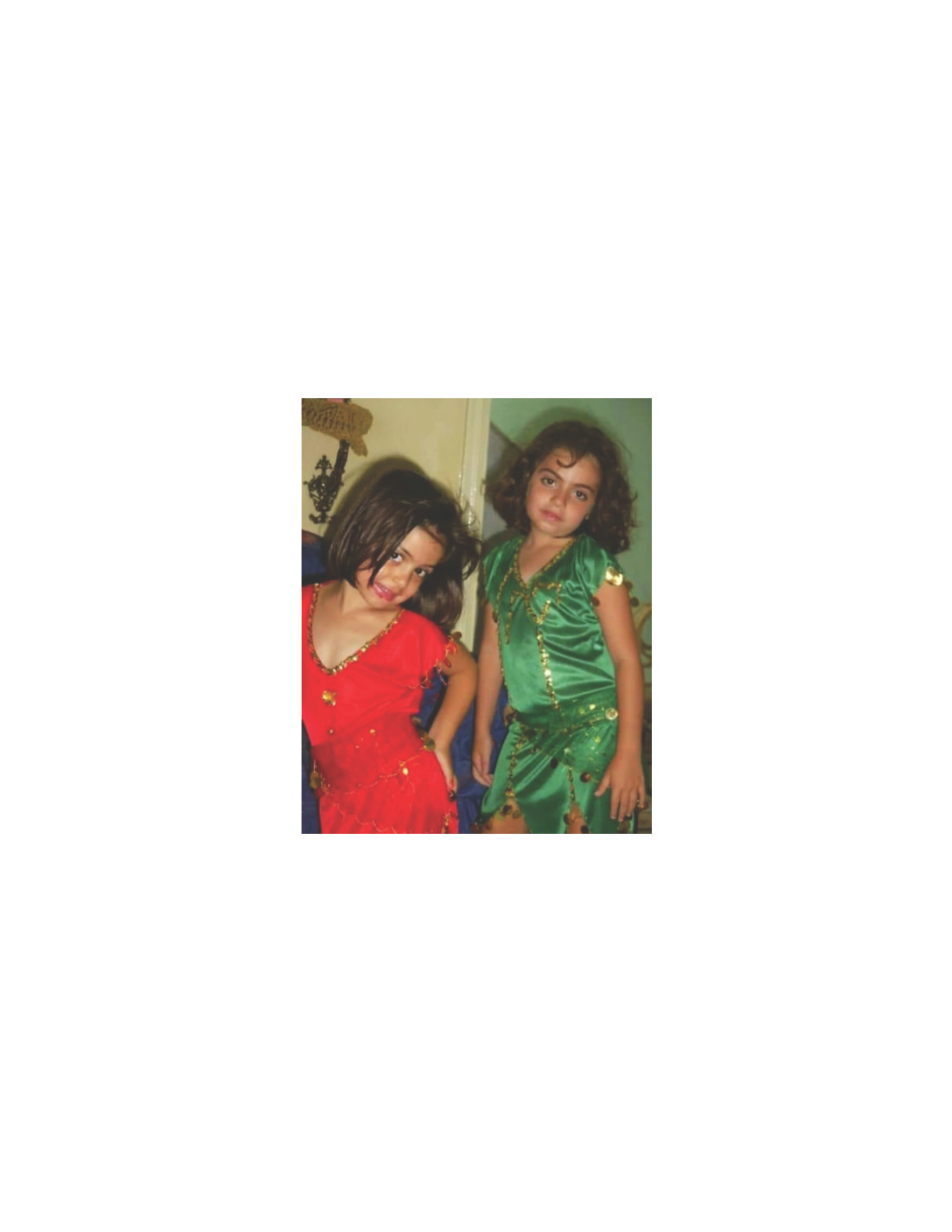

One of the earliest memories of my childhood is my sister and I trying on belly dancing attire in Damascus, Syria, and trying to move our hips and shoulders to the beats vibrating off of my cousin’s darbuka. At that moment, for us, it feltlike we were at the center of the world. With each sway of the hip, my grandma would let out a zalghouta and my aunt would say our names to get our attention to capture a tiny fragment of the small piece of happiness and hope that existed around us.

On July 12, 2006, everyone in Lebanon woke up to the sounds of bullets and explosions marking the start of the “July war” between Hezbollah and Israel. My parents grew up inward. This meant that, whether there was political tension or not, our pantry was always stocked with rice, wheat, canned foods, and other preservatives. Just in case. We had learned how to survive. To stay safe, my mom would setup mattresses in the hallway of our tiny apartment. In that area, my parents always made sure that we had no paintings, hanging lights, glass, or anything that might fall and break if there was an explosion. For weeks, all four of us would sleep there. At some point, after a while, my parents realized that what was happening was more than unrest. It was a war. We packed our bags and tried to cross our way to Syria where the rest of my dad’s family lived. At the border, we were stopped. They let my sister and father go but my mother and I had to return to Beirut. I don’t have the answer to why they did that. Borders, for people like us, are warzones of their own. We cannot ask questions. A few weeks later, we were reunited in Damascus and stayed there until the war ended.

My name is Karni Keushgerian and I am an international student from Beirut, Lebanon. This is my second year at SLU and in the United States. Like most international students, my experience has not been easy.

A week ago, I refused to sing a song that carried implications about Israel because of my political beliefs. My life experiences have led me to live my life breathing in everything as if it were political. Singing that song, for me, meant taking a political stance. Singing that song meant turning a blind eye toward lyrics that were encouraging a political situation that led me to sleep in bomb shelters as a child and as an adult. I am tired of being put in positions where have to explain my discomfort in order for it to be valid. My trauma is only accepted when I am writing college applications but is immediately rejected when it means that another person is uncomfortable with it. I doubt that the person I had this conversation with was aware of all this and that they were doing it on purpose to create tension. However, this is an accurate depiction of how the responsibility for calling out a wrong is put on international or BIPOC students. The outcome of this conversation was a White, American man telling me to “go and do more research before making a decision.”

There are a lot of things that can be said about this response. My primary issue with the United States has been the entitlement that exists within its White culture. However, intertwined with this entitlement exists a cloak of invisibility. The White supremacist culture that has shaped this nation has cast a spell upon its people claiming that their privilege gives them the right to be the Self and, everyone else, an Other. Anyone who is non-White is an Other. Moreover, everyone who is a tokenized “Other” simply becomes a statistic that is said in pride during events like matriculation and graduation. We are tired of fulfilling the gaps in White knowledge. We are retired of existing in spaces on White terms that do not cater to us. Within the last week, a staff member mimicked my accent, and another White faculty member said the N-word in class. To what extent are international and BIPOC students protected from the lack of willingness of both faculty and the student body to make this space inclusive?

Microaggressions are a part of our daily experience as international and BIPOC students. All our identities are different, granted. This fact does not entail, in any way, that we have the power to understand each other. Furthermore, this does not mean that in order for us to be able to solve the political implications that come with attending a PWI, we need to understand each other. The “diversity quota” that I fill and the “diversity course” that you take to fulfill your requirements do not exempt you from your complicity in making SLU an uncomfortable space for many of us. In many courses and classes, “foreign literature” and “foreign policies” are perceived and taught as exoticized concepts that only exist in the outside world, far from the United States. To a certain extent, this is true. In education, there is always a fight between the local and the global; however, the problem with institutions like ours in the United States is often forgetting that the global is the local. Every time a US citizen votes for a political leader, they are electing a global dictator. Every time a US citizen protests against injustice, they are protesting against injustice globally. The imperial power the United States has on the world is overseen as a reality that is far from the control of individuals. Isn’t this ironic? Isn’t it ironic that I come from a country that has experienced US-American war crimes but is also expected to adopt the image of an ideal international student by reaching for every opportunity, being grateful, and getting the highest grades I could get? BIPOC and international students must work harder to reach for the things that some people might be given. This is because, for us who come from marginalized racial and ethnic groups, every single step we take is a fight against local and global imperialism. A type of oppression that people forget about after counting us and putting us in their annual display of diversity statistics.

I have often been called “emotional” or “too political.” The reason for this is that people are uncomfortable with some of the thoughts that we, as BIPOC and international kids, voice. People don’t want to hear how we do not enjoy school choirs because all the songs are 200-year-oldEnglish songs. People don’t want to hear how our professors make us uncomfortable by being insensitive and exclusive with the content they teach. People don’t want to learn how to pronounce our names. People don’t even know where our countries are on a world map. We shouldn’t only be voicing our opinions when we are fuming with anger. Articles like this one should not only be featured when it is the last resort to our exhaustion. By being here, what kind of education are we advocating for? What do we all want? How can we make this space safer?

Firstly, build a relationship with organizations and groups on campus that people like us are comfortable with. Do not just collaborate but initiate and interact. Second, put in an effort. Think twice about what you want to say and how you want to say it. Throw events and start conversations that go beyond your perception of how the world looks like. Expand your spaces. Invite people in. Do not assume that BIPOC and international students are a means to an end. Weare not vessels that exist to fill in gaps in your knowledge. Frankly, we are burnt out. We do not have the energy to constantly fight against homesickness, financial difficulties, microaggressions, racism, and ignorance. We are tired.

Lastly, while thinking about this, do not just implement actions to prove a point and put on a show. Our identities should not be victims of performative, White positionality. We are not puppets. You reading this is not you saving us. You being inclusive is not a fight toward forced political correctness. It is okay to make mistakes. It is okay to explore. Just like we have learned to adapt to your spaces, we ask that you respect ours. This is not easy but it is most definitely, human. Be inclusive for the purpose of building a community that is for all of us. Be inclusive for the sake of you and me both