The first image of a black hole has finally been captured after years of work by researchers around the world, a breakthrough that has truly excited the scientific community.

Joey Neilson of Villanova is a black hole researcher who used Chandra, a type of x-ray imaging, to observe the pictured black hole, M87, at the same time the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) was used in creating the image. “We used to say you’d never actually be able to take a picture of a black hole. You’d need a telescope the size of the Earth to see it,” he says.

According to Neilson, to make the image possible, the EHT Collaboration realized that they could build an Earth-sized telescope by linking radio telescopes around the world. They made extremely precise measurements using eight radio telescopes simultaneously. “This was hard. It took a decade of planning and upgrading the radio telescopes,” he says.

A lot more than just a telescope went into the imaging. Aileen O’Donoghue, an astronomy professor at SLU, explains that the telescopes only give voltage, which has to do with how bright the object it’s looking at is. “They have all these combinations of observations, but they have to create this image from them,” she says.

O’Donoghue explains that what Katie Bouman, a postdoctoral fellow on the project, noticed and incorporated into her coding was that looking at a given pixel and looking at its neighbors, the neighbors are not too different from that pixel. Because of this insight, they were able to stitch the picture together.

This black hole, M87, has a mass of 6.5 billion suns, so it’s very heavy but its radius is actually smaller than the orbit of Pluto, according to Neilson. However, O’Donoghue says that what is really seen in the image is not the black hole itself. “The black hole is actually absorbing light from behind it, so we’re seeing the shadow of the black hole,” she says.

The bright circle surrounding the black hole in the image is called an accretion disk, says O’Donoghue. The huge gravitational pull from the black hole makes everything in the galaxy want to fall into it, and when things fall they spiral around and inwards before actually going into the black hole, she says. The image shows the black hole almost head-on, according to O’Donoghue, and “the brighter particles in the accretion disk are coming toward us while the dimmer are moving away.”

Nick Knudsen, a self-proclaimed astronomy expert, believes that the image is important for a multitude of reasons. “What I really appreciate about it as a data science major is the amount of analytics that went into creating this one image,” he says. Although, according to O’Donoghue, “we have no idea what applications the computing and science learned from this will have.” However, she also asserts that this type of basic research is certainly worth doing “because we don’t know what it’s going to do.” She says it’s about exploring and seeing what might

come from what we find.

“What is so astounding to me is the fact that Albert Einstein, 111 years ago, wrote a paper on general relativity that predicted the existence of black holes—something that no one could have ever imagined. A point where nothing could escape from—what would that even look like? And the theory arose because of the math that he asserted and now, 111 years later, we’ve confirmed that exact assertion with a direct image,” Knudsen says.

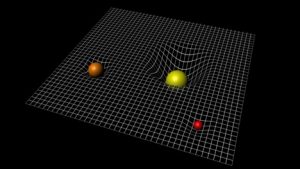

Despite the image confirming their existence, black holes are still a difficult concept. Claire Bartlett, a SLU astronomy student explains them well. She says that the universe is like a sheet of fabric with balls on it, and when one is too heavy, such a deep hole is created that nothing in time and space can escape falling towards the gravity of that mass. The formation of this black hole arises from the death of a star. Neilson explains that “a star is basically a huge nuclear explosion, and when it runs out of fuel to burn, it goes supernova and collapses under its own weight. If it’s massive enough, what’s left will be a black hole.”