St. Lawrence is a home of African exceptionalism. Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and Obiora Udechukwu have all graced this campus, a place that seems far removed from the African continent but through these personal links still embraces the significance of “Africa.” Each visiting African has paved the way for the next, softening the cold and hardened grounds for African roots.

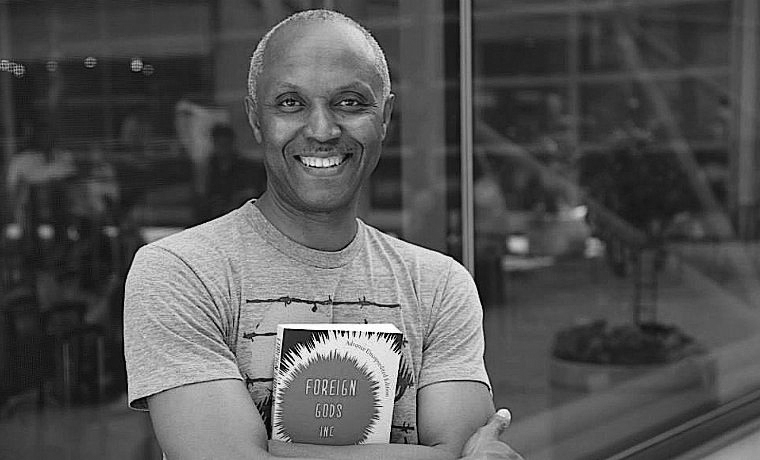

Through this process SLU has welcomed Okechukwu (Okey) Ndibe: a master of words and the Viebranz Visiting Professor of Creative Writing. Beyond his books, articles, and interviews, Ndibe is an assemblage of stories and a generous orator. As a previous student of his, I can attest to his generosity and push for participation in class. My first class with him was a session of storytelling. Each student had to tell a story close to their hearts and through that we became equal citizens with collective appreciation.

Class was more about sharing than anything else. We were often whisked away by stories of his travels, famous friends, and comical childhood. Every word that he shared meant something, and every statement was upheld by facts and principles.

In his novel “Arrows of Rain”, Okey writes “Remember this: a story that must be told never forgives silence. Speech is the mouth’s debt to a story.” And Okey has paid many debts and continues to do so.

On February 2, the campus experienced the power of stories as Ndibe read from his two books: “Never Look an America in The Eye” and “Foreign Gods.” In between readings, he continued his tradition of sharing stories. His stories highlight the importance of love, the continuous struggle against African stereotypes and how upbringings shape people.

The Chapter chosen from “Never Look an America in The Eye” explored the difficulty of departing from the status quo as a new immigrant in the United States. In the chapter, Ndibe shares his experience with a police officer in Amherst, Massachusetts. He highlighted the false assumption that even if a police officer addresses you as “sir,” and asks “do you mind?” it does not mean that he holds you in high regard and will treat you as a “sir.” In fact, the propriety of police officers is in direct opposition to their oath of honor

. Okey Ndibe was later falsely arrested. Upon his release, he requested the police officer to return him back to the same spot he was arrested, so that those who witnessed his arrest would recognise his innocence and perhaps think that policeman was his friend and they just went for a beer.

Following this, Ndibe’s second reading from “Foreign Gods” questions why the gods of the west are invisible. Shouldn’t an omnipotent deity be able to materialize himself and garner belief? The chapter explores the intercultural experience of an Igbo man who questions the authenticity of a Christian god. Especially when his Igbo god has a physical location for the Igbo man to visit and share his tribulations as well as offer sacrifices.

These brief glimpses into his life and books emphasize the importance of political fiction, especially when writers hail from outside the concurrent hegemony.

These were many teachings to take from the event: Okey Ndibe loves Sheri Fafunwa-Ndibe, stories are opportunities for connection, and for those who attended the event, without crocodiles, Okey Ndibe and the other Africans on campus would not be at SLU today.